monitorACT - September

13.09.21

Editorial

Capture. Feminine noun meaning the act or effect of capturing. Apprehension. Imprisonment. Conquest. Seizure. Confiscation. Impounding.

The meanings of capture are some of the words which can be used to define the movements we have seen made by giant corporations concerning causes or actions enabling them to improve their image before the consumer, and eventually sell more products. Whatever these products may be, to whatever public. Sales are what matter, and to convey the impression that they are offering help above any type of suspicion. We also see movements to capture ideas, as if ideas needed to be stored in tightly sealed boxes, so they can’t go out and win people over, who may one day question and change structures.

The capture of ideas has been taking place through education, based on childrens’ initial development, and is portrayed in When agribusiness comes to school, which shows how movements connected to the agro sector are infiltrating schools and higher education courses. Based on this infiltration, coordinated and streaming throughout the country, the manipulation of groups of students’ parents occurs, surveillance of schoolbooks, persecution of publishers and teachers, interference in the school curriculum. The intention is not to allow antagonistic points of view of the sector to prevail. “Agro is pop”, as repeated by the TV advertisement, it creates jobs, generates wealth, feeds the country, that must be the mantra to be repeated indefinitely, without any questioning, and for the population to think this way, it is necessary to act on the formation roots.

In Revolving doors and multi-stakeholder governance models: a critical view, we discuss the asymmetric influence by private companies in relation to other social actors, especially in major negotiations involving public policies. In this political capture, decisions regarding the drafting of and changes to laws, which are the duty of the Legislative Branch, their interpretation and enforcement, competency of the Judiciary Branch, and the design and execution of public policies, a task for the Executive Branch, are influenced in order to favor profits. It is possible to realize that nothing significant will change in food systems, for example, as long as companies that manufacture products that are damaging to health and the environment are sitting at the policy negotiation table.

Hunger: a political choice for governing authorities shows the capture of a cause, of the well-being and health of a nation as a whole. The text deals with food insecurity, which already affects at least 50% of Brazilians, whereas its most serious form, expressed by hunger, is felt by 19 million people. Companies invest in solutions aiming to save the lives of starving children in contexts of war or calamities. Who would oppose gestures such as these, the authors ask, and immediately explain that the issue is all about patents, meaning that people who wish to produce their own product based on local products or produce cannot do so.

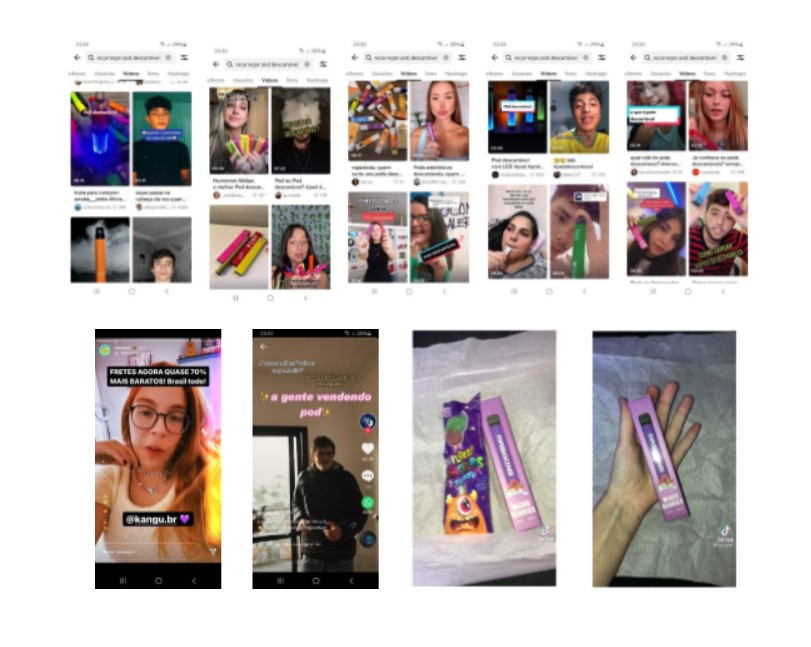

Lastly, we experience the capture of time, of fun, of entertainment, through social media. And in a way, the capture of young adults for new tobacco products. In TikTok: where anything #goes, the authors present impressive data on the promotion and sales of vaporizers, electronic cigarettes or pods, as they are called, on the Tik Tok platform, an absolute success among people up to the age of 34. This time the youths are not only the target audience for marketing, but they themselves are promoting and selling the products, besides arousing interest among children, who are able to receive the goods packed together with candy and become loyalty customers.

Enjoy your Reading!

Anna Monteiro

Communications Director

Hunger: a political choice for governing authorities

Vitoria Moraes and Camila Maranha

Brazil is going through an unfortunate situation where public policies related to food and nutrition sovereignty and security have been dismantled since 2016. The adoption of a neoliberal agenda resulted in the neglecting of social needs, such as the Human Right to Adequate Food and Nutrition, a fact exacerbated by the pandemic brought on by Covid-19.

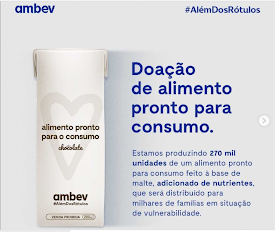

Faced with the emergency situation of food insecurity which already affects half the population of Brazil and hunger impacting 19 million people, major companies have decided to invest in solidarity programs, through food collection campaigns and donations.

Ambev went one step further. The company launched a malt-based liquid chocolate food product, with added nutrients, for donation. With sales prohibited, units of the product were distributed to families in vulnerable situations in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, previously assisted by the Center for Favelas (Central Única das Favelas - CUFA) and the Gerando Falcões Organization. According to Ambev, after many different studies and analyses, which were not mentioned, it was possible to deliver a so-called highly nutritious product, rich in vitamins A, B6, D and E, a source of vitamins B1 and B2, calcium and magnesium with added vegetable protein.

The Bodies in Dispute (Corpos em Disputa) episode from the Full Plate (Prato Cheio) podcast, from O Joio e O Trigo, makes it clear that this is not a new strategy. The episode mentions the product called Plumpy Nut, made by French company Nutriset. It is a kind of peanut butter with added vitamins and minerals, with the objective of treating children in a situation of severe malnutrition with most of its production destined for Unicef. It is a product for therapeutic use which is considered emblematic in the fight against hunger, which should be used when there is no possibility to prepare natural food, which has also been highlighted in advertisements for humanitarian aid groups such as Doctors Without Borders. Researcher Marion Nestle cautions that defending food products such as Plumpy Nutt, destined to save the lives of starving children could even resemble a theme for which there could be no controversy. After all, who would oppose something like this? The question to be asked is not who, but when would anyone oppose this? The answer is simple: when there are patents involved, meaning that people wishing to produce their own commodity based on local ingredients, cannot do it.

The question surrounding the development of so-called miracle products is tied to a reductionistic viewpoint of the hunger issue and actually of food itself. Seeing food as a big combo of nutrients, whose only purpose is the functionality of the organism, excludes all other senses of food, moving through factors such as history, culture, attachment and ancestry. Even so, major companies in the food and beverage sector have increasingly been viewing this type of action as a practise worth investing in, beyond the benefits of improving image and reputation in itself, but also due to the fact that families in a vulnerable situation represent a potential group of future consumers. This is described in a documentary called Obesity Industry (original german title “Globale Dickmacher”) by Joachim Walther, where strategies by the industries are shown to attract the low income population towards the consumption of ultra-processed products, declining to consume local traditional food.

It is worth mentioning here that Ambev is one of the most profitable food and beverage sector companies in Brazil, not just through product sales, but also through million-dollar subsidies and tax evasion. According to an investigation in O Joio e o Trigo, the company has already made savings of R$ 2.8 billion in national taxes, while the budget set aside for food security and nutrition policies has been drastically reduced in the last five years. It’s an interesting fact, since food is a permanent and regular constitutional right guaranteed by the State, and donations are of an occasional and voluntary nature. Therefore, large food donation campaigns should not be seen as the only tool for fighting against the food and nutrition insecurity scenario.

The path taken by Brazil on the way to leaving behind the Hunger Map, between 2003 and 2014, was the result of multidisciplinary and well-articulated policies, based on an expanded view of the problem. By viewing and understanding hunger as a social issue, investments were made in measures aiming to increase family income and reinforcing family farming policies, in addition to creating the National Food and Nutrition Security System (Sistema Nacional de Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional - Sisan), composed by the Food Security Councils (Conselhos de Segurança Alimentar - Consea), at the local and federal level, representing a type of living expression of democracy.

The 2014 Food Insecurity Report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which mentions Brazil as an example to be followed vis a vis the fight against hunger, highlights the implementation of policies which are not limited to food, but have direct impact on the standard of living for families, such as increasing schooling for mothers, increasing basic care coverage and sanitation conditions. Hunger is a political choice for governing authorities. We currently see the increase in power for transnational food companies, while society’s food sovereignty is undermined, since many families do not have the right nor power to choose what goes on their table. Brazil has already faced the hunger issue through the strengthening of horizontal policies, such as the National School Feeding Program (Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar) and the Food Procurement Program (Programa de Aquisição de Alimentos), without the need to become a hostage of solutions which act on the problems superficially, suggested by the private sector.

The results from the Family Budget Survey (Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares - (POF/IBGE) for 2017-2018 point out that most Brazilians still uphold nutrition based on in natura (raw, natural) foods, as suggested by the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population (Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira). Additionally, the country possesses endless knowledge related to land use and food production which need to be highly valued and encouraged. Small producers find difficulty to convey their products and little incentive to continue producing food.

In the Facing Hunger Through the Strength of our Struggles (Enfrentar a Fome com a Força das Nossa Lutas) manifest, many organizatons have shown that one must not be deluded by false solutions. Culture, knowledge and paths allow feasible possibilities of healthy and sustainable food systems and public policies that assure rights, food being one of them. “We need to join the people of the lands, waters and forests, united in solidarity and communion for rights, democracy, sovereignty and food and nutrition security”.

TikTok: where anything #goes

Victoria Rabetim and Mariana Pinho

Electronic cigarettes, which their consumers refer to as vapes, pods, disposable pods and other nicknames, are different electronic devices that work with many systems and whose function is to provide nicotine to their users. This substance causes a feeling of pleasure and wellbeing because it acts on the brain, and for that reason, is responsible for chemical dependency. This means that its consumers, throughout their lives, will feel the need to consume higher doses in order to experience the same feelings from back in the initial, experimental phase, and when they go without it, they will experience an unpleasant sensation, known as withdrawal symptom. This is what happens to nicotine addicts, both smokers and vapers.

We should not underestimate the effects of nicotine on the human body, as the manufacturers of these products do. In addition to dependency/addiction, the substance is linked to the development of lung and cardiovascular disorders and are related to carcinogenesis – accelerating the process of cancer development. Studies have shown that users have a higher dependency level than conventional cigarette smokers. This happens because the nicotine in these devices is modified. Users absorb much higher amounts in their lungs more easily.

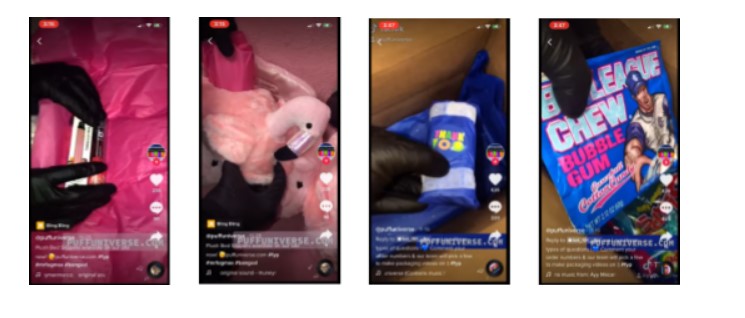

Promotion strategies for these products, even during the pandemic, have been registered by civil society organizations and researchers in Brazil, the USA and other countries in the Americas. An article published in January 2021, on a website focused on technology news, as well as profiling companies, products and websites, shows TikTok users in the U.S. advertising and selling these products. The text goes on to reveal the tactics employed in order to send the products in the mail to children and teenagers in “parentproof” packaging, in other words, the report picked up the fact that the vapes were mailed concealed among sweets and candy or inside slippers.

These products came onto the market in the U.S. without any kind of regulation; for that reason, they grew into a mania especially among teenagers. In 2018, e-cigarette use went up by 78% among high school students nationally. However, as we were concluding this edition of MonitorACT, we got news that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibited sales of electronic cigarettes produced by JD Nova Group LLC, Great American Vapes and VaporSalon, because “no evidence was presented showing that their products would be beneficial enough in order to overcome the public health threat represented by the alarming and well documented levels of use of such products by youths”.

Medical students in Mexico conducted surveys on the Tik Tok platform and found a lot of advertising, special offers and discounts, as well as promotions involving digital influencers and well known figures in the country.

Here in Brazil, even with their sales, advertising and import forbidden by Anvisa, approximately 700 thousand Brazilians in the 15 to 24 age group use electronic smoking devices (Dispositivos Eletrônicos para Fumar - DEF). Thus, a quick scroll through TikTok using the words pod, vape or vapebr, shows a very concerning scenario and similar to the U.S. and Mexico. This reinforces the fact that there is a global strategy used to promote these products.

The mindset behind TikTok is different than other social networks. In this network, it doesn’t matter how many followers you have, but the “story” you tell on the platform. The content is not limited to the network of profile followers, various elements are relevant for the app to deliver the content to more people; one of them is for the content to be happy, joyful. This is possible due to the network’s extremely “refined” algorithm, which understands the user’s interests in great detail and shares what is relevant to him/her. Half of network users claim they use the platform to have fun and cheer up and two thirds of users create content within TikTok.

When it comes to consumption, according to TikTok for Business itself, 66% of users agree that the platform has helped them decide on what to buy, 67% have been influenced to shop even when they didn’t have that objective and 74% have said the platform helps them with ideas about brands and products which they hadn’t thought of before. There are 3.5 billion #TikTokReviews, in other words, product assessments from the point of view of their users. Over 50% of the public shares product assessments on and off TikTok.

Additionally, TikTok is the social network where users remain connected for the longest period of time: 6.16 min per session, almost double the time of runner-up Facebook with 3.28 min per session. The average app use time is 64 minutes per day.

The TikTok community is very active and engaged and includes 80 million active users every month, 186 billion monthly video views per month and over two billion downloads all over the planet. With regard to user age groups, 60% are aged between 18 and 34, of which 32% aged between 18 and 24 and 28% between 25 and 34. Around one out of every four users is aged 17 or under. The majority of the public is formed by women: 65%.

A quick search through different hashtags associated to DEFs lay wide open the level of reach achieved by these products promoted on TikTok. #vape videos have already reached over 5.2 billion views, #vapetricks – the tricks with vapor produced by vapers – has 1.5 billion and #vapes has had 197 million views. These figures refer to views around the world. If you search the pod descartável (“disposable pod”) hashtag, in an attempt to filter Brazilian videos, numbers between 2.2 million (#podsdescartavel) and 9.9 million views (#poddescartavel) come up. For #cigarroeletronico, the number is 14.8 million.

It is worth mentioning that the company guidelines state that the following are prohibited: “the presentation, promotion or sales of drugs or other controlled substances. The trade of tobacco products and alcohol is also forbidden on the platform. (...) Do not post, send, stream or share: Content which offers to purchase, sell, trade or request drugs or other controlled substances, alcohol or tobacco products (including vaping products).”

Although the public on the platform is not known, it is surprising that youths are not only targeted through the marketing of these products, but they themselves are promoting and commercializing the pods. The amount of viewed content with hashtags related to the word “vape” is overwhelming. In addition, they arouse the interest of minors who manifest curiosity about the products and interest in purchasing them, and can receive the vapes together with candy and establish loyalty relationships through multi-purchases.

Last February ACT launched Immediate Delivery Addiction (Dependência à Pronta Entrega), a report on tobacco product sales through delivery apps and forwarded it to the authorities responsible for reporting and issuing fines for such irregularities. Advertising for any tobacco product on the internet is in breach of Federal Law 9294/1996 and ANVISA (National Agency for Health Surveillance) resolutions. It is also an insult to the international treaty, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, of which Brazil is a signatory together with 180 countries and the European Union.

These findings reinforce what has already been established by evidence and disclosed by secret documents in the tobacco industry. Transnational companies that sell products containing nicotine aim for a very specific target: young people. They are the potential customers for companies which will substitute smokers who give up smoking or die prematurely due to it. Platforms and social networks must be jointly made accountable for acts which infringe national laws.

When agribusiness comes to school

Priscila Diniz

Recent data released by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply shows that Brazilian agribusiness has never seen this level of growth and should achieve its all time highest earnings still this year, around 10% higher than in 2020. We see, therefore, sector enthusiasts celebrating earnings which have almost tripled in the last two decades, indicating that agribusiness is on the way to its first trillion mark. Those defending the sector also use data provided by the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation – Embrapa – which pointed out that Brazilian agro feeds 800 million people. The methodology used, however, did not consider the complexity of how the global food system works.

If on one side everything portrays sunshine and farmed land, the dark side shows up through another survey, the National Survey of Food Insecurity (Inquérito Nacional sobre Insegurança Alimentar), which shows that 56% of the Brazilian population is subjected to some level of food insecurity, and approximately 19 million Brazilians literally starve. The euphemism regarding the subject of starvation becomes even clearer when reports are shown depicting absurdities, such as the increase in sales of instant noodles, an ultra-processed food product, and people buying bones and meat leftovers to make soup, as reports recently exposed.

Statements that Brazil feeds the world are highly strategic to agribusiness and usually appear linked to its grandiose contribution to exports and accountability for GDP growth. It is also possible to note insistence on the idea that by intensifying the use of technology in the countryside, production will become increasingly sustainable end environmentally friendly and that the sector is a job creator.

These arguments divert the focus from the tax privileges that benefit the sector and accusations of conflicts and extermination of indigenous peoples and traditional communities, intensification of environmental degradation and the direct relation to global warming.

As criticism mounts up, companies comprising the sector try to improve their image and win over public opinion as early as possible. Thus, the entry of agribusiness into Brazilian public schools starts to take place.

The first advances were made towards the end of the 1990s and beginning of the 2000s, when the image of agribusiness had been strongly tainted by the connection with slave labor and mainly, by the massacre that had occurred at Eldorado dos Carajás. A clear attempt to provide an ideological response to dispute this narrative was through the introduction of programs to divulge agribusiness in schools different than what was shown on the news. Today, it is already possible to identify at least 14 different programs.

The formulator of the inaugural program was the Brazilian Agribusiness Association (Associação Brasileira do Agronegócio - ABAG), who started the Agribusiness in Schools Education Program (Programa Educacional Agronegócio nas Escolas), developing projects in thousands of municipal schools in the São Paulo State school network. The Program enabled these students to be in touch with a different historical narrative about agro, and thus put out an image of progress to society, especially in provincial towns with fewer inhabitants. The proposal was never to improve schools or education itself, but to disseminate, under a collaborative guise, what education sector intellectuals call “hegemonic pedagogy”, in other words, conquering group adoption first for or through one’s class and if possible for all of society.

With regard to these programs, we highlight here two of the main movements, but there are many others in the picture. Starting with the most recent, called “With an Eye on the Schoolbooks” (“De Olho no Material Escolar”), which started around October 2020, organized in about twelve states in Brazil, gathering a few dozen people in its political core, who were divided into work committees and operated at a local level; others, nationwide. These initiatives seek to create or encourage movements dedicated to the surveillance of schoolteaching material, bringing together people connected to agribusiness who are dissatisfied with the image presented in schools. The proposal is, then, in an orderly manner, to receive this material, make complaints and report teachers.

The materials received differ greatly from each other, which shows a high degree of capillarity and ability to monitor content in different towns, cities, regions and states in Brazil. The catalog undergoes a categorization of themes and editors of school material, which in sequence are put under pressure through letters requesting reviews or receiving rejection letters.

It is also possible to identify programs such as “Experiencing Practise and Building Knowledge” (“Vivenciar a Prática e Construir Saberes”) and “Agrinho” (“Little Agro”), which consist of inviting teachers and students to visit agriculture and cattle farming, agroindustrial or industrial production units related to agribusiness and convincing them that what is depicted in books does not represent the full facts or is obsolete.

At the national level, where there is greater impulse for the initiative due to its comprehensive nature, we find liaisons with schools of higher education such as ESALQ (Luiz de Queiroz School of Agriculture), which formalizes the strategy that until the contents are not altered to a satisfactory level, a virtual library is to be built in order to house the contents challenging them that may be used in order to be provisionally conducted. There is also a liaison through the Institute for Agriculture and Cattle-farming Studies (Instituto Pensar a Agropecuária - IPA) and the Agricultural Parliamentary Front (Frente Parlamentar da Agropecuária - FPA), approaching the Ministry of Agriculture, in order to ensure that everybody is well informed in this trio, which has been united and articulated in a permanent communication channel for a long time. An action has already been identified, as it happens, through the Agribusiness Higher Council of the São Paulo State Federation of Industries (Conselho Superior do Agronegócio da Federação das Indústrias do Estado de São Paulo -Fiesp).

Such moves are public-private and exercised through a large variety of representative entities, culminating in direct influence and pressure on each one of the publishers whose teaching material has upset heads of agribusiness. All it takes is an outraged mother or father whose son or daughter is using the teaching material at their school, accompanied by a technical member from ESALQ to provide the technical support for the argument, and the assault on the educational material commences. At the center of all this we also find the National Schoolbook Program, as shown by an assessment made by the Brazilian Geographers’ Association. With the seemingly harmless fragmented and disorganized report networks, a situation ends up being imposed on the teachers: adhere to agribusiness or be denounced by it.

The second most prominent movement identified is called All In One Voice (Todos A Uma Só Voz). Led by companies in the industrial sector, mainly those who despite having a dominant voice in agribusiness, are more subject to strategic risks in the face of environmental destruction as well as being on a collision route with other rural representatives who publicly defend the government’s current environmental policy. Among them the Brazilian Association of Food Industries (Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Alimentos - ABIA), who leads the proposal, but also other organizations that do not have a declared position criticizing the government’s environmental policy and feel negatively affected by some of the actions. It is a widespread movement, which also supports and is connected to the aforementioned De Olho no Material Escolar, but seeks to consolidate a participation in education by investing in its offensive towards public opinion in the school environment.

In both cases, the movements are strongly interconnected, which affords them strength and influence capability, not only by agents exerting pressure at the local level, but also by those collecting materials passing them on to an organized national base to summarize them for the national process. This is followed by meetings between private agents, behind closed doors, with the Education Ministry (MEC), to also discuss teacher training, in a profound process of interference in Brazilian education.

By way of an attractive, interactive and didactic approach and in the void left by the instability and scrapping of public schools, under the justification of the current negative rates and levels of education, the permanent capture of curriculums and political and education projects takes place, with foundations and private interest institutions taking on the role of training public sector educators in municipalities, especially in the more provincial areas where there are actors from rural social movements.

The tactics employed by these movements are very similar to those in Draft Bill 7180/2014, attributed to Schools without Parties (Escola Sem Partido), which calls for “ensuring the diversity of ideas in teaching and preventing teaching staff from harming students due to their political, ideological, moral or religious convictions”. To education specialists, however, there are veiled aspects that accompany this discourse, revealing its undertones of censorship and accountability of teaching staff members.

Revolving doors and multi-stakeholder governance models: a critical view

Laura Cury and Paula Johns

In August of last year, then World Trade Organization (WTO) Director-General Roberto Azevedo announced that he would take on the Vice-Presidency position of food giant PepsiCo, one year before the scheduled end of his term at one of the most important multilateral organizations. In an official announcement, Azevedo said that he was delighted to be joining PepsiCo, referring to the snacks and beverages manufacturer as “a world leader for the promotion of major collaborations and investments focused on improving our society and planet”, according to media reports.

The position, at the time recently created for Azevedo at PepsiCo, gathers public policies, government and communication issues under the same umbrella, to consolidate the company’s external engagement with a number of governments, international organizations and non-government stakeholders.

It is not uncommon for politicians, government regulators or heads of major international organizations to leave their positions at international agencies to go on to lead a major company. More recently, the former head of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Scott Gottlieb also took on a Board member position at Pfizer. These are examples of what is commonly referred to as “revolving doors’, a term used to describe when somebody who has held a government position moves to the industrial sector, or vice versa. We already commented on this in a 2019 publication.

Source: https://review.chicagobooth.edu/public-policy/2017/article/should-we-stop-revolving-door

Behind the revolving door, we come across the idea of political and regulatory capture. This practice results in an asymmetrical influence of private companies in relation to other social actors. In the practice of political capture, decisions regarding the drafting and modifying of laws, which are the duty of the Legislative Branch, law interpretation and enforcement, which are the competency of the Judiciary Branch, and the devising and execution of public policies, the role of the Executive Branch, are influenced so as to benefit the profit of specific economic actors.

We notice this phenomenon taking place in the health sector more frequently than it should, and a survey carried out by the São Paulo School of Medicine among executives makes this practise very clear. These executives formerly ran the Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária - Anvisa) and the National Supplementary Health Agency (Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar - ANS) which they went on to leave to work for companies which they used to regulate, with financial transactions of over R$ 270 billion in 2019.

This corporate capture also happens at the international level, which shows an absence of effective global regulatory mechanisms to create equal conditions for competition among States, placing company interests before public interest.

Large corporations support several international organizations, such as the World Trade Organization, going as far as the functioning of the United Nations (UN) Organization. According to Friends of the Earth International, “major corporations take on a privileged advisory role, United Nations officials move back and forth from the private sector, and their agencies are more and more financially dependent on the private sector. One additional cause for concern is the emergence of an ideology among some UN agencies and their staff, according to which, “if something is good for the companies, it is also good for society.”

It is not uncommon for multinationals, many of them with a history of human rights violations, including the right to adequate and healthy food, health and to a protected and safe environment, to sponsor some of the main UN events, or show up as partners in the projects of many of their agencies. The idea of a multistakeholder governance model is recurrent in international negotiations. This structure of governance brings together the parties that are interested in a certain theme, including companies, to take part in the dialog, in the decision-making process and in implementing solutions to common problems, which means bringing major companies to the negotiating table to solve problems in the public interest.

l

Source:http://www.vigencia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Vige%CC%82ncia_Cata%CC%81logo_FINAL-1.pdf

Another example of political capture takes place within the realm of the UN Food Systems Summit, a meeting created to discuss issues, present scientific approaches and introduce agreements on how food systems can be a way to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to famine, inequality, agriculture, consumption and climate by 2030. There is a trend observed where major corporations co-opt multilateral spaces to address our fragile food systems. For the Summit to be held, a strategic partnership agreement was established between the United Nations and the World Economic Forum, who granted transnational companies preferred access to the UN system, which demonstrates incoherence, to say the least. Global leader on sustainable development and Columbia University Professor of economics Jeffrey Sachs drew attention to the fact in his presentation at one of the preliminary meetings, stating that we have a global food system, but we need a different one: “We cannot hand over the global food system to the private sector. We already did that around 100 years ago (...). We find ourselves in an extremely difficult world. The private sector will not solve this problem. I’m sorry to say this to all the private sector leaders here. What is key for the private sector is simply this: behave, pay your taxes and follow the rules. That is what companies must do.”

The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO/FCTC), the first international public health treaty, is a model which can be extended to other areas. FCTC article 5.3 is clear with regard to transparency and social participation in decisions related to public policies, as well as imposing limits on the participation of major corporations in decision-making areas related to their own activity.

The “I’ll Believe It When I see It” (“Só Acredito Vendo”) campaign, which brings together organizations from many sectors, touches on this theme by reporting tax breaks reaching up to R$ 300 billion per year for Brazilian companies and demand information about where this money goes. It is an example which shows that the role of civil society and the academic sector must be to denounce this agenda sequestration and demand transparency, for this is the only way to safeguard public assets from co-option by what is in the private sector.

Review and editing: Anna Monteiro

Art direction: Ronieri Gomes

Monitor team

Anna Monteiro

Bruna Hassan

Camila Maranha

Denise Simões

Fabiana Fregona

Laura Cury

Mariana Pinho

Marília Albiero

Victoria Rabetim

Vitória Moraes

Collaborated in this issue: Priscila Diniz